April Op-Ed - Sweet spot for the hawks

- 27 April 2022 (7 min read)

Key points

- Hawkish rhetoric ramped up at the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB), fuelled by resilience in the real economy.

- Cracks are appearing in the outlook though.

- A potential adjustment for US stocks relative to bonds and other equity markets is underway

- Some ongoing premium for superior earnings performance in US stocks is likely justified

- But if the Fed is serious about squashing inflation, tighter financial conditions could mean US equities are one of the biggest victims.

Don’t look down

Central banks are in a “sweet spot” right now to ramp up their hawkish rhetoric. The tailwind from the post-pandemic reopening is still there – and sometimes powerfully so, in sectors such as recreation and tourism – while the fiscal stance remains – for now – supportive. In Europe this still “drowns” the impact of the spike in energy prices triggered by the Ukraine war. On both sides of the Atlantic, business confidence remains robust.

This allows monetary policy to focus on the risk of persistent inflation. In the US, the strong prints in consumer prices – the plateau in core inflation in the March data was entirely attributable to the gyrations in one item, used cars – combined with strong wage growth is pushing the Federal Reserve (Fed) into a “hawkish escalation” almost on a daily basis. It seems a consensus is forming on bringing the Fed Funds’ rate close to “equilibrium” (c. 2.0/2.5%) by the end of the year already. Note that since this would be combined with a reduction in the central bank’s balance sheet at a faster pace than in 2018-2019, the overall monetary stance would tighten hard and quickly.

Lagarde had managed to steer a cautious normalization path at the latest Governing Council and reiterated her views in subsequent interviews that the nature of the inflation shock was different across the Atlantic Ocean (no second-round effects from wages can be detected in Europe) and that “an ECB hike would not reduce the price of oil”, but this prudence is conditional on the materialization of bad news on the real economy side. With no obvious signs of materialisation – for now, the hawks, who in the case of Isabel Schnabel explicitly consider the current fiscal stimulus “fuels the fire” of inflation, have an avenue to call for quicker normalization. Consequently, we had a flurry of comments pointing to an early and/or brisk pace of policy tightening from several Governing Council members. Luis de Guindos and Martins Kazaks have both mentioned the possibility of a rate lift-off in July already, while Pierre Wunsch stated that a deposit rate “at zero or higher by year-end was a no-brainer”.

Yet, we are starting to see some “cracks” in the dataflow in the US, as consumer confidence dives, reflecting the decline in real income. Indeed, even the spectacular acceleration in nominal wages is not keeping up with consumer prices. The Fed’s rhetoric has already pushed market rates higher and with flagship mortgage rates now exceeding 5%, the flow of new property loans is decelerating quickly. In Europe, the resilience in the data is conditional on governments continuing to spend profusely to offset the rise in energy prices, which is going to be increasingly difficult as the support from the European Central Bank (ECB) via quantitative easing is close to its end.

Finally, the impact of the zero-Covid policy on China is becoming very visible, even if we are still a long way away from the collapse in activity seen in early 2020. Political authorities find themselves facing the same kind of trade-off western countries had to deal with over the last two years: opt for generalized lockdowns and accept a significant economic fallout or tolerate significant mortality. Since China has not materially tapped its “policy reserves”, eschewing the kind of massive fiscal stimulus accommodated by monetary policy which has been generalized in the West, while a significant fraction of China’s older population is not vaccinated, the choice should be obvious, and for now, restrictions remain severe. According to a Bloomberg article from 14 March, only 51% of people over the age of 80 have had two vaccinations and only a fifth have had a booster. For now, although consumption is struggling, taking services down, China’s “producing machine” looks intact and trade data for March suggest the country remains able to meet world demand, which is good news for supply-side constraints in the developed nations. Still, if restrictions were to tighten further, it’s difficult to imagine that manufacturing would not be affected as well.

Navigating the second half of the year may be more difficult for central banks. We would add that in the Euro area, fragmentation issues – in clear, a significant widening in sovereign spreads – may return as the ECB terminates QE. The bond market has welcome Christine Lagarde’s readiness expressed at the last press conference to “design and deploy” anti-fragmentation weapons if and when necessary. She was remarkably guarded about the form that such programmes could take though. It’s understandable given the technical and political difficulties already faced by the ECB in the past when designing tools to specifically address monetary policy transmission impairment, while it was preparing to normalize its stance. We go back in time to 2010/2012 and the debates around the Single Market Programme (SMP) and Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT). The latter – although never used – has been seen for 10 years as the “go to” anti-fragmentation weapon. But it is cumbersome, even if alternatives are not necessarily appealing. We note however that there is an imbalance between what the ECB is being asked to do – create more Ptolemaic circles around its core missions to deal with every shortcoming of monetary union – and the contribution from national governments. In 2012, the solution to the sovereign crisis did not come solely from the ECB, but also from the governments’ capacity to put together new frameworks, such as the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). We continue to think that without an extension of Next Generation EU, the ECB may be forced into “half solutions”, such as mobilizing the reinvestment from the QE programmes to support the most fragile signatures.

The end of cheap money and the risk to US equities

The post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) delivered an unprecedented period of easy monetary policies. The key beneficiary of super-low interest rates and quantitative easing was the US equity market. It has significantly outperformed equity markets elsewhere in the world. The policy stance also shifted the traditional relationship between equities and bonds. It drove down the discount rate and guaranteed liquidity in bond markets, allowing equities to continuously re-rate without a financing constraint. Re-allocation away from ever lower yielding Treasury bonds into corporate debt was facilitated by the attraction of a credit spread backed by an implicit put option. Investors in multi-asset portfolios relied less and less on the traditional hedging characteristics provided by Treasuries as monetary policy itself provided the hedge. The result has been no lasting set-back in US equity markets since the GFC. Is now the time we get one?

Inflation is now at its highest for decades. The era of cheap money is over and the US equity market is perhaps the most vulnerable to the change in regime. While QE was not confined to the US, it had more of an impact on equity valuations than anywhere else. In Europe, the ECB’s QE was geared more toward staving off a sovereign debt crisis. In Japan, deflation pre-dated the GFC so even with zero rates, nominal growth and earnings expectations were too low to generate decent returns in equities. It’s true that equities have outperformed bonds in those regions and that the traditional cyclical relative performance between risk and risk-free assets was dampened by QE. The impact was the most extreme in the US. Today the gap between the forward earnings yields and the yield on 10-year Treasury note is just 2.5%, compared to an average of 4% over the last two decades. Elsewhere in the world, the gap is bigger – which is to say equity markets outside the US are relatively less expensive.

Ben Bernanke famously once said if you reduce the discount rate to zero then the discounted value of future cash-flows goes to infinity. The pandemic took this to an extreme. The liquidity provided in early 2020 and the subsequent stimulus to demand from fiscal policy catapulted equity valuations to new highs. A potentially more significant equity correction after the 2015-2018 tightening cycle was avoided by the rapid deployment of economic and market supportive measures once COVID became a major threat. But that was then and now the bond market is pricing in significant monetary tightening over the next year or so.

Inflation is the central problem for the Fed and, in the US at least, it is a demand as well as a supply problem. The Fed can’t do anything about supply, but it can use monetary policy to slow demand. This is the key risk for the US equity market. If the Fed raises rates enough in the US to generate below trend-growth to reduce inflation, it will have a global impact. Corporate earnings will suffer, and equity markets will have both lower earnings and a higher discount rate to contend with.

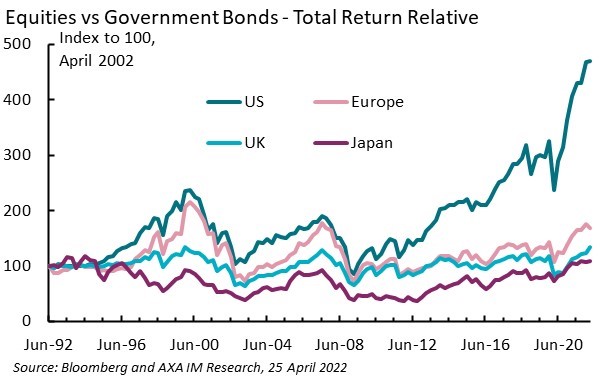

We could see a return to the pre-GFC relationship between equities and risk-free rates. Yields are already almost as high as they were in the last monetary cycle. In the recessions that followed the 1999-2000 and the 2004-2006 tightening cycles, bonds significantly outperformed equities in the US and elsewhere (Exhibit 1). The sell-off in fixed income markets so far this year has raised the chance of something similar happening should monetary policy become restrictive and trigger a recession in the US. Of course, the starting point in terms of yield is much lower but in the absence of central bank ability to revive QE because of inflation, the potential for negative equity returns is clear.

Exhibit 1 - Equities have outperformed bonds in the QE era

The question for investors and asset allocators is whether the inflation problem is serious enough to call time on QE and the associated financial repression. If central banks lose their nerve, inflation will stay higher and that scenario deserves some consideration of what to hedge. We continue to see the benefit of having inflation-linked bonds in mixed portfolios given that inflation indexation is going to remain significant for a while. If tight labour markets, elevated energy and food prices and growing evidence of second-round inflation effects force central banks to really turn the monetary screws, then the risks are clear to see for equity investors.

Globally, equity markets outside of the US are less expensive. However, we note that earnings momentum is turning negative and 12-month forecast growth rates are coming down. Many markets have already corrected by more than 10% from their cyclical highs, some more than 20%. But the US market’s correction has been limited in the context of how much super-accommodative policy in 2020 pushed up valuations. To some extent, the US market deserves a valuation premium given its historically superior earnings performance, which we expect to continue. However, this has increased in recent years and if the Fed really is serious about squashing inflation, the US equity market might well be the biggest victim.

Disclaimer

This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment research or financial analysis relating to transactions in financial instruments as per MIF Directive (2014/65/EU), nor does it constitute on the part of AXA Investment Managers or its affiliated companies an offer to buy or sell any investments, products or services, and should not be considered as solicitation or investment, legal or tax advice, a recommendation for an investment strategy or a personalized recommendation to buy or sell securities.

It has been established on the basis of data, projections, forecasts, anticipations and hypothesis which are subjective. Its analysis and conclusions are the expression of an opinion, based on available data at a specific date.

All information in this document is established on data made public by official providers of economic and market statistics. AXA Investment Managers disclaims any and all liability relating to a decision based on or for reliance on this document. All exhibits included in this document, unless stated otherwise, are as of the publication date of this document.

Furthermore, due to the subjective nature of these opinions and analysis, these data, projections, forecasts, anticipations, hypothesis, etc. are not necessary used or followed by AXA IM’s portfolio management teams or its affiliates, who may act based on their own opinions. Any reproduction of this information, in whole or in part is, unless otherwise authorised by AXA IM, prohibited.