Principles Matter

- 11 May 2020 (7 min read)

Key points

- The ECB will probably refrain from endorsing the German Constitutional approach. Technical solutions exist but the conflict is about principles. The ECB will want to protect its independence and the unicity of monetary policy.

- Together with renewed tension in the Euro area, persistent EM weakness and the return of US/China tensions are our top concerns for the recovery in the second half of 2020.

Most continental European countries have by now relaxed the conditions of their lockdown to some extent or are about to do so. We continue to expect a much better second half of 2020, but we are concerned by three forms of “backlash” which could impair the recovery.

Renewed tension in the Euro area, given the asymmetries we have already discussed in Macrocast, is the first one. The ruling by the German constitutional court last week - which would force the Bundesbank to stop contributing to one of the QE programmes if the ECB fails to show its action is proportionate - is a significant hurdle. We explore how the central bank could technically “do without the Bundesbank” and still provide protection to the most fragile countries. But fundamentally the legal conflict is about principles, and we fail to see how the ECB could submit itself to the GCC process without jeopardizing its independence and the unicity of monetary policy in the Euro area. True, it is high time anyway to relieve the ECB of its burden and solidify the monetary union with some form of fiscal mutualisation but the Eurogroup meeting last week did not make progress on the “Recovery Fund”.

Persistent weakness in emerging markets is the second form of “backlash”. Most of these countries have embarked on policy stimulus but their constraints are often much tighter than for the developed markets. Some of them are now also experimenting with QE, and this comes with specific risks and limitations.

The last item on our list is the resumption of tension between the US and China. The world could definitely do without commercial tensions emerging just when global trade may tentatively re-start, but it may be too electorally tempting for President Trump. China exited the lockdown earlier than the developed economies, but its economy remains subdued. So far it has refrained from embarking on “all out” stimulus. The perspective of more tension with the US may spur more fiscal and monetary action.

See you in Court (or not)!

Tension within the Euro area is the first item on our “backlash list” which may imperil the post-lockdown recovery. This could be pre-emptively addressed with either unconstrained monetary stimulus or robust fiscal mutualisation. The German Constitutional Court (GCC) ruling on the ECB’s Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) puts the first solution in jeopardy, while the Eurogroup’s meeting on 7 May did not bring about any breakthrough on the second.

The GCC’s ruling would prevent the Bundesbank from participating to PSPP - as well as force it to divest the government bonds it has acquired so far - if the ECB fails within three months to satisfy the German authorities that its programme complies with the principle of “proportionality” (in a nutshell they did not balance the impact of their programme on the whole economic spectrum against the benefit in terms of monetary policy objectives), as it considers that the European Court of Justice (ECJ) has failed to correctly check this in a preliminary ruling.

The ECB first needs to choose whether to respond to the GCC and demonstrate the proportionality of its action. A debate among economists has started on this. H. Siekman and V. Wieland from the University of Frankfurt for instance proposed last week to integrate the “proportionality issue” in the ECB’s policy review to placate the GCC.

It always makes sense for the central bank to explain its policy, and Christine Lagarde made plain her willingness to reach out to civil society when designing the ECB’s strategy. But we think that Siekman and Wieland err when they argue that after all, the GCC judges are “also members of civil society” and as such should be the recipient of policy justification. Indeed, the Court is not a part of civil society like any other because it has the power (or considers it has the power) to stop a component of the Eurosytem - the Bundesbank - from participating to a joint policy. There is a difference in nature between explaining one’s policy and submitting such policy to some post-approval by a national court, especially after the ECJ – which is in charge of the legal control of the ECB – has already ruled in favour of the policy. This would open the door to an infringement of the ECB’s independence.

On substance, “proportionality” is a particularly problematic concept in the case of the ECB because we would argue that by nature its mandate is “disproportionate” as per the European Treaty itself. Indeed, Article 127 gives the ECB the mission to deliver price stability in the Euro area while it shall support “the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union” only “without prejudice to the price stability objective”. This should make it clear that price stability - which means in the current circumstances fighting deflation risks - trumps ANY other consideration.

To make this more concrete, we could look at historical precedents in which this absolute dominance of the price stability mandate was controversial. The GCC argues that the ECB failed to demonstrate it took on board the interests of the savers when making its PSPP decisions. Without discussing here the relevance of this argument, what would have happened if in July 2008, when the ECB raised its policy rate at the beginning of what was to become the worst recession since 1945, a court in one of the member states had threatened to force its national central bank not to apply the new rate, because the ECB had failed to demonstrate it had taken on board the interest of those who were about to lose their job because of such pro-cyclical monetary policy?

Independence does not mean that monetary policy cannot be discussed, sometimes robustly (and to be clear your humble servant considers that the 2008 decision was a massive policy mistake). But there is a joint decision centre for this - the Governing Council - and a joint institutional forum - the auditions of the ECB President at the European Parliament. And finally, there is the informal court of public opinion. Submitting the ECB decisions to the interpretation of the EU law by national courts would quickly make a single monetary policy impossible.

How to navigate out of this predicament?

We think that to explore this fundamental but horribly complex situation it may be handy to distinguish two interconnected issues, first the “purely German” side of the equation – how to deal with it within the institutional set-up of Germany – and second the “European side”.

On the first point, there is quite some hope in the possibility the German government and parliament could merely declare themselves satisfied with the proportionality of the ECB’s action, based on the existing communication from the ECB, possibly with some support from the Bundesbank (which would allow the ECB “proper” to remain one step removed from the GCC). Reuters reported last Friday that such action had already been taken by the Ministry.

This may not suffice however. Indeed, the GCC has raised the bar quite high as to how it could be satisfied by the ECB’s justification. Indeed, point 235 of the GCC ruling calls on the “ECB Governing Council [to] adopt a new decision that demonstrates in a comprehensible and substantiated manner that the monetary policy objectives pursued by the ECB are not disproportionate to the economic and fiscal policy effects resulting from the programme”. This is quite precise.

We also need to consider the medium-term implications. Indeed, even if the GCC ultimately found PSPP compliant with the Treaty’s prohibition of monetary funding of governments, its ruling also potentially set up several “red lines” to the ECB’s future action which so far were deemed to be “self-imposed” and hence susceptible to amendment. This applies in particular to using the “capital key” to apportion purchases across national markets and 33% as the maximum share of the eligible debt of a sovereign issuer the ECB can hold. The GCC made it plain that its ruling does not apply to PEPP, but more lawsuits are likely to come.

This, plus the possibility that the GCC paves the way for more dissenting interpretations of EU law in other member states, probably calls for some clarification by the EU institutions – the other side of the equation. The ECJ asserted its pre-eminence on the interpretation of EU law last Friday in no uncertain terms, by issuing a press release: “In order to ensure that EU law is applied uniformly, the Court of Justice alone – which was created for that purpose by the Member States – has jurisdiction to rule that an act of an EU institution is contrary to EU law”. The European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen stated on Saturday that the “Commission is looking into” the possibility of suing Germany for treaty infringement.

In a nutshell all the ingredients for a protracted legal conflict are accumulating. This was brewing for some time since the GCC had always taken the view they had the possibility to independently check whether European institutions exceed their mandate (act “ultra vires”). It is a pity this is coming to such a frontal state at a time when ECB support is particularly necessary.

Now, what would happen in practice, if the Bundesbank ended up being permanently barred from participating to PSPP? This component of the ECB’s quantitative easing effort is at the moment smaller than the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, but the Governing Council would probably refuse to stop it altogether. Massive purchases are even more vital after the GCC ruling, and we suspect the main reason why the Italian spread did not widen more at the end of last week is precisely because the ECB is buying a lot on this market. We could think of two technical solutions to “do without the Bundesbank”.

One would be to ask another national central bank to replace the Bundesbank and buy Bunds. This would allow the Eurosystem to continue operating under the “capital key” but quite quickly they would hit the 33% threshold on German debt. Presumably, assuming economic conditions still warrant it, they would continue buying Bunds, taking in practice very little risk (the probability of default of Germany being infinitesimal, there is very little chance the Eurosystem would find itself in a position of being the “deciding force” in a debt restructuring). They would thus continue to support more fragile countries for which the 33% threshold is still far away.

Another one would consist in simply stopping purchasing Bunds while continuing buying the other member states’ securities. It would de facto be the end of the capital key condition, but this would also allow a very decent quantum of additional buying in the other constituencies until again the 33% limit is hit there as well.

The second solution, combined with the Bundesbank gradually selling the Bunds it has purchased under the PSPP could create quite an odd configuration for market interest rates in the Euro area, with peripheral yields under protection but at the same time potentially higher yields in Germany.How to navigate out of this predicament?

In a way, one could see “continuing without the Bundesbank” as a strangely powerful way to deal with the limitations of quantitative easing, by the same token allowing political authorities in Germany not to be forced to make domestically controversial decisions. Berlin could even officially disagree with the next steps taken by the ECB but without having any actual impact on how monetary policy would be conducted. ECB action would be merely constrained by the European Court of Justice, which so far has granted the central bank quite some leeway (the only “hard” limit which we think we could derive from its previous rulings on QE is that the ECB could not hold a majority of bonds).

It would still be a very awkward political situation, unlikely to instill confidence in the monetary union construct, that the central bank of the biggest economy of the Euro area would no longer participate to a central plank of the single monetary policy.

Fundamentally, it would be preferable to relieve the pressure on the ECB by stepping up efforts on fiscal mutualization. This would entail parliamentary endorsement in member states and hence support the development of what is yet an incomplete European political space, rather than resorting to an unelected body – the central bank – to shoulder most of the burden. The Eurogroup last week made progress on the specific pandemic loans which member states will be able to obtain from the European Stability Mechanism without the usual macroeconomic conditions. Their long duration – 10 years – is good news as it will help government cash flows but capped at 2% of GDP, they can’t be the main solution. The Recovery Fund still needs to be defined. Maybe the growing awareness among the “frugal states” that the ECB’s capacity is not infinite – at least not without triggering some thorny legal and political issues – will speed up the process.

QE goes global

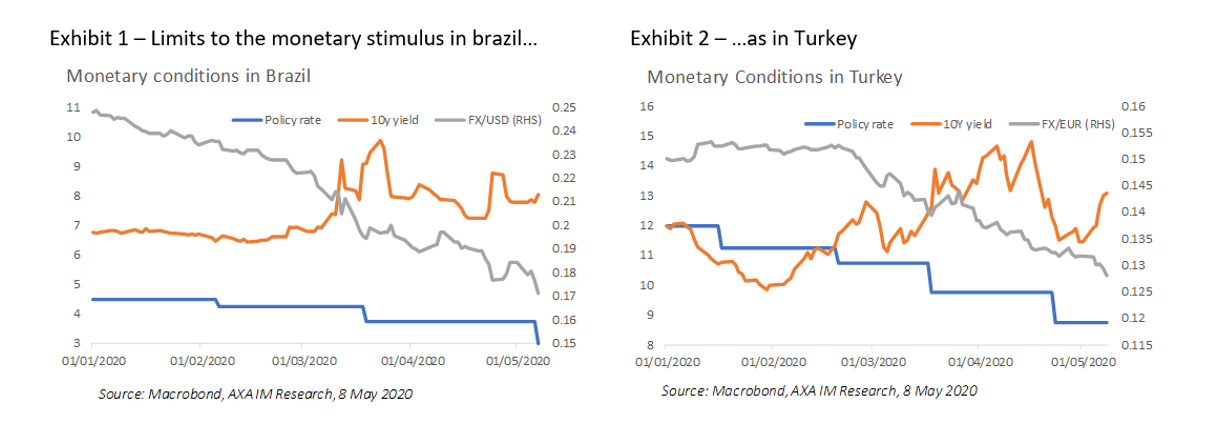

Persistent weakness in emerging markets demand is the second item on our “backlash list”. There just like in developed markets a massive monetary stimulus is underway, but limits to central bank credibility and dependence on external capital inflows affects its efficiency. Focusing here on Brazil and Turkey, expansionary monetary policy did not trigger a loosening in financial conditions across the whole yield curve as it did in the developed markets (see Exhibit 1 and 2).

Both countries are now supplementing traditional monetary policy with quantitative easing. The central bank of Turkey has bought a record quantum of nearly EUR5bn of government bonds since the end of March – with only limited result (at the end of May the 10 year yield was lower than at the April peak but still noticeably higher than before the pandemic). In Brazil, the central bank has been granted permission to engage in QE only last week, since this took a constitutional amendment.

The central bank of Brazil (BCB) intends to be very prudent. The BCB President Roberto Campos Neto stated that purchases of longer-dated bonds to bring down yields would “ideally” be offset by the sale of short-term bonds. Campos Neto is clearly concerned with the risk of turning what is for now a necessary reaction to an emergency into a systematic form of financial support to the government, cancelling all the progress achieved in terms of macro management in his country since the 1990s. The risk is not theoretical since the BCB is not yet independent from the government. The President has introduced a bill to this effect in parliament in April, but the process has not concluded.

The generic “risk-off mood” triggered by the pandemic, combined with policy accommodation, political tensions and doubts on macro-management ahead are behind a steep depreciation in EM currencies (see again Exhibits 1 and 2). More than proper macroeconomic stimulus, QE – which is spreading throughout Latin America - could be in the case of EMs an emergency solution to substitute the central bank’s balance sheet to disappearing foreign investors.

The impact of such FX movements on financial stability has changed a lot since the EM crises of the 1980s and 1990s. Most of these countries have been able to reduce the share of the external debt which is denominated in foreign currency – it is the case in Brazil for instance - but the issue has not completely disappeared. In Turkey for instance, according to S&P, loans denominated in foreign currency stood at more than a third of total domestic loans last year. This creates a clear limit to the local stimulus. Beyond those risks, FX depreciation in EM countries depletes their external purchasing power, which is bad news for the developed countries which have become increasingly reliant on EM demand as trend growth has been slowing down in the North.

US-China tensions re-emerging

The last item on our “backlash list” is the return of tension between China and the US. At the beginning of the pandemic, President Trump had been sympathetic to the plight of China. The tone has certainly shifted. Re-igniting tension is a temptation for the incumbent as the November elections are looming. It is a double-edge sword. Indeed, adding to the shock of the pandemic more uncertainty on global trade may alienate the moderate voters chiefly concerned with the state of the economy. Still, now that Joe Biden is leading in the polls in almost all the crucial “rust belt” states, Donald Trump may want to focus again on a theme which resonates with blue-collar voters.

This would not help China. Indeed, so far Beijing has not engaged in the form of extreme fiscal support which has been so prevalent in the West. After the “mechanical” rebound March the recovery is now subdued, judging by the usual indicators such as the PMIs. The labour market is being rattled everywhere, but in China 170mn migrant workers were among the worst hit by the production suspensions in many low-paying jobs, and 25mn people who left for home before the lunar new year did not return to work by the end of Q1. Household income per head has fallen by more than 4% year-on-year in real terms. Beyond the domestic headwinds, given the severity of the anticipated global recession, a 20% fall in China’s exports, similar to that seen during the global financial crisis, may be conservative. A resumption of trade war on top of this would be particularly averse to any significant rebound in investment.

The Politburo – the main policymaking committee –is now putting “protecting job market stability” ahead of a numerical growth target as this year’s top economic task. We therefore expect Beijing to announce further and significant policy easing measures at the upcoming National People’s Congress meetings in late May specifically to address rising joblessness. Monetary policy is also likely to loosen further. We note that the quarterly monetary policy report dropped the point on “avoiding excess liquidity flooding the economy” in its latest issue.

Not for Retail distribution

This document is intended exclusively for Professional, Institutional, Qualified or Wholesale Clients / Investors only, as defined by applicable local laws and regulation. Circulation must be restricted accordingly.

This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment research or financial analysis relating to transactions in financial instruments as per MIF Directive (2014/65/EU), nor does it constitute on the part of AXA Investment Managers or its affiliated companies an offer to buy or sell any investments, products or services, and should not be considered as solicitation or investment, legal or tax advice, a recommendation for an investment strategy or a personalized recommendation to buy or sell securities.

It has been established on the basis of data, projections, forecasts, anticipations and hypothesis which are subjective. Its analysis and conclusions are the expression of an opinion, based on available data at a specific date.

All information in this document is established on data made public by official providers of economic and market statistics. AXA Investment Managers disclaims any and all liability relating to a decision based on or for reliance on this document. All exhibits included in this document, unless stated otherwise, are as of the publication date of this document. Furthermore, due to the subjective nature of these opinions and analysis, these data, projections, forecasts, anticipations, hypothesis, etc. are not necessary used or followed by AXA IM’s portfolio management teams or its affiliates, who may act based on their own opinions. Any reproduction of this information, in whole or in part is, unless otherwise authorised by AXA IM, prohibited.

Issued in the UK by AXA Investment Managers UK Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK. Registered in England and Wales, No: 01431068. Registered Office: 22 Bishopsgate, London, EC2N 4BQ. In other jurisdictions, this document is issued by AXA Investment Managers SA’s affiliates in those countries.